This blog is mainly about two things: My life as a treehugger, and my life as an urban designer. This explains why my posts switch back and forth, focusing at one time on the city in which I live and then another on how I strive to live an eco-friendly, compact life. This particular post, is a quick snippet into some of my "green" habits that are ridiculously easy for anyone to pick up! It all goes back to the bathroom!

Gross! No, not at all. You'll find very little toilet talk in this post- I'll save that for a later time. All I want to do right now is show you some products you can purchase which make bathroom activities environmentally friendly (I promise, one day I'll talk about green cleaning!). These products are: Preserve's toothbrush, Ecover Toilet Bowl cleaner, Biokleen's drain cleaner, Preserve's razor, and castile soap.

1. Preserve's Toothbrush: What subscriptions do you keep in your bathroom? Time magazine? The Local News? Playboy!? Too personal, sorry. Well I only have one, but it's a different sort of subscription. It's my toothbrush! The handle of the Preserve toothbrush (I've chosen blue) is made from 100% recycled materials, specifically yogurt cups {vegan yogurt!? I wish!}. The bristles, of course, are new. With a subscription, you'll get four toothbrushes (either every 3 months, every 2 months, monthly, or all at once) and in exchange you return your toothbrush via the package in which your new one arrives. You can mail back their store-bought brushes, too, but this is so much easier- and no more forgetting to change your toothbrush! I have the 3 month program, and I love it! Sign up for your own Preserve Toothbrush Subscription!

2. Ecover Toilet Bowl Cleaner: As I mentioned above, I promise to one day write a post on how to clean your home without using harsh chemicals, but today, I have to products I'd like to mention. I use my own homemade toilet bowl cleaner most of the time. When I was living alone, that was perfect, but now that I live with my fiance, the task of cleaning a toilet has become even more dreadful. My solution? Use a store-bought cleaner ever so often, and in between cleans use my homemade recipe. I tried a few different products before I settled on this one. A while back, when my mom and I lived together, she bought Clorox's Green Works products. They worked fine, but I just don't trust Clorox to be environmentally friendly. It is a legitimate cleaner, it bears the Sierra Club mark of approval, and it contains no bleach, but it wasn't sold in health-food stores, and that did it for me. After testing a few more products, I settled on Ecover's product. It's eco-claims sold me: "Plant-based ingredients — not based on petrochemical ingredients; no

chemical residue; optimum level of biodegradability (far exceeds

legislative requirements); safe for river and marine life; no animal

testing" That list of "eco-claims" comes from Grist.org's review of toilet cleaners, and they are awesome selling points. If you check out Grist's list, you'll see their only complaints were the scent and the fact that the liquid was clear. To be honest, the scent is refreshing (they say pine but I think it's more like peppermint) and the fact that it's not an eerie blue color reminds me that there are no scary ingredients in this product! I give it two thumbs up! Do your own research at the Ecover website!

3. Biokleen Drain Care: Okay, again, cleaning recipes come later. I do want to point out that you can unclog your drains using household ingredients, but that doesn't always work as awesome as I'd like it to. So I had to resort to a stronger concoction. Enter Biokleen Drain Care! I've used Seventh Generation, I've used Earth Friendly Products, I've used Mrs. Meyer's (side note- is Mrs. Meyer's actually eco-friendly? I need to do more research)....non have worked that great. Biokleen's drain cleaner is good with regular use, but you do have to work at those tough clogs! Still, I recommend it! Here's Biokleen's website for you to look over.

4. Preserve's Razor: Back to the really exciting stuff! Did I mention I love Preserve!? I don't think I did, but they're a great plastics company, for all you plastic lovers out there. For things kitchen and bath related, they've got tons of recycled plastic products for you! This little guy is great. To be honest, it's blades could be better designed, but the fact that it's made of recycled yogurt cups is just terrific!

5. Castile Soap: Last but not least (and there are actually millions of other green bathroom products I could talk about), we have castile soap, specifically, Dr. Bronner's in (my favorite) peppermint scent. As a vegan, I am very pleased to tell you that castile soap, unlike other soaps, is made without animal fats! Who would want to clean with animal fat anyway!? How is this used in the bathroom, you ask? Toilet cleaner, counter cleaner, floor cleaner, spray cleaner, body wash, hand soap, shampoo, teeth cleaner...you get where I'm going with this, right? It can be used for practically anything. Thus, I love it. Especially in the bathroom! I have liquid and bar soap forms in my bathroom. Check out all the other awesome products made by Dr. Bronner's.

There are a plethora of environmentally friendly products to use in the bathroom, these are perhaps just my personal top 5! The important thing to remember in the bathroom is that your drains lead somewhere! Imagine all the chemicals and crap (no pun intended!) that escapes through your drains each day- we have to take responsibility for all of that! All that gets washed away ultimately ends up in our rivers and oceans. So from now on, get clean with the cleanest products you can find! From shampoo and soap to toilet and sink scrubs, there's an alternative out there. Find what works for you and stick with it!

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Filling the Void on Howard Street Baltimore

A Study of Emptiness and Finding Purpose Along

Baltimore City’s Historic Corridor

Once a vibrant and

busy destination, Howard Street now functions simply as a means for passage

through, into, and out of Baltimore City. By intimately studying the blocks

between Fayette and Monument Streets, one might catch brief glimpses of the

lively street that once was. Most of what’s left standing today, however, tells

a rather unfortunate story of a neglected and forgotten corridor. Borrowing

from the processes outlined by urban theorists before me, I have used various systems

to evaluate the physical form as well as the expressive essence of Howard

Street. From such vigorous analyses, I have identified a combination of grounds

for explanation as to why the corridor is, or is not, functioning in its

current form.

As a Baltimore

County resident, I often use the light rail line to travel into the city. As it

enters Baltimore’s central neighborhoods, the light rail settles into the

Howard Street right-of-way. In my years of riding, I have developed a sort of fondness

for one stop in particular. At the corner of Howard Street and Centre street,

the light rail drops its passengers off a few blocks west of Mount Vernon, just

south of the Cultural Center, one stop north of Lexington Market, and nearby to

downtown Baltimore. Yet it was never because of this stop’s close proximity to

such amenities that drew me in; it was likely more about the adjacent park, or

perhaps the fact that this particular light rail stop always had a sense of stillness

to it, that I took the opportunity to step off the train. From the intersection

at Monument Street, just north of the Centre Street light rail stop, down to

the next light rail stop on the 100 block at Fayette, Howard Street has a very

distinct character. My study of the corridor encompasses these six blocks, with

heavy focus on the three northernmost blocks from Mulberry to Monument. Systems

of evaluation- such as Kevin Lynch’s visual mapping; Emily Talen’s approach to

transect classification; the Venturi and Scott Brown system of signs and

symbols; and indeed Anne Whiston Spirn’s study of nature within the city- shall

provide an opportunity to peel back the layers of the city to reveal the

fundamental nature of Howard Street.

An Area of Historical Relevance

|

| Howard Street, Looking North at Lexington; Photo Credit: Baltimore County Public Library Legacy Web |

The department

stores and theaters have since shut down; only the Market continues to operate

today (at 230 years old, it is the longest running market in the world), but fading

signage lingers as a reminder of what once was. The evolution, or perhaps

decline, happened slowly throughout the twentieth century as the corridor was

altered little by little. In the 1930s, even amidst the Great Depression,

Howard street was still a robust, and vibrant destination. Howard Street at

Lexington was, at the time, a major intersection and in 1934, Read’s Drug Store

was constructed on the southeast corner. Twenty-one years later, in 1955, Read’s

would be the site of an early sit-in of the civil rights movement, which has since

given Howard Street profound social significance.[1] Five

years before the well known Greensboro sit-in, a group of Morgan State

University students made a powerful statement when they organized a successful protest

at the Read’s Drug Store lunch counter (Pousson 2011).

|

| Read's Drug Store on Howard Street; Photo Source: Baltimore Heritage Website |

While Howard

Street was doing well during these years so, too, was the automobile which made

traveling outside the city an efficient alternative. With this convenience, the

new shopping malls were able to flourish. As more and more city residents

traveled to the outskirts of Baltimore to shop in these new malls, Howard

Street became less and less relevant, yet managed to remain economically stable.

In 1942, the Greyhound Bus Terminal was built at Howard and Centre Street (Vandervoort

n.d.).

Howard Street was to be enhanced by a new bus route, a future that was never

realized. This building still stands today and is part of the Maryland

Historical Society’s campus. The Maryland Transit Administration entered the

picture in the 1980s with the introduction of the light rail line. Although it

provided an inexpensive means for residents to travel within and around the

city, there has been a general consensus that the transportation “improvements”

of the light rail have been the main cause of Howard Street’s demise.

The booming activity of old Howard Street may be gone, but the physical

form remains. Many of the buildings which directly front the street retain

architectural details that can so rarely be found on buildings constructed

after the 19th century. Sadly, behind these magnificent facades, the

buildings crumble in disrepair. Like the Mayfair, whose roof collapsed in the

1990s, these buildings sit as abandoned shells, waiting for the next tenant to

come along and embrace their history; but it’s been years since anyone’s seemed

interested. While people have all but forgotten, nature has slowly begun the

process of reclaiming the land upon which these buildings sit. A future similar

to the one explored by author Alan Weisman in his book, The World Without Us,

is developing before our eyes. As human activity continues to neglect the few

blocks surrounding Kernan’s Corner, nature- as I’ll soon explain- finds new

ways to make its presence known.

Methodology for Deeper Appreciation

Methodology for Deeper Appreciation

Although I have been

to Howard Street many times before, I had never delved so deeply into its story

as I did upon my initial study visit. During this trip, I utilized photo

documentation and visual mapping techniques, in conjunction with notations of

any emotions felt along the way, to document the corridor. The goal was to be

truly within Howard Street’s fabric

as opposed to just passing through it, as too many people often do. Traveling a

total of ten blocks between Martin Luther King Boulevard and Baltimore Street, I

made a point to patronize local establishments and talk to any willing

passerby. The subsequent visit entailed a much more elaborate process of evaluation,

which proved to illustrate very interesting results.

|

| A Collection of Urban Study Methodologies |

Very little that

exists on Howard Street is consistent from Monument to Fayette. Street art, however,

is surprisingly abundant along the entire stretch. These images carry heavy

messages, which make them particularly intriguing. As I was studying one of the

first pieces I encountered, I paused photographing so as to greet a passerby.

The man said hello, continued walking to the opposite end of the block, then reversed

course with extreme purpose. He marched back to where I stood to ask me why I would

photograph this image which he didn’t find to be especially alluring. I’m very glad

he decided to speak with me, for our long discussion of art proved quite

enjoyable and as testimony of art’s power to bring strangers together. Art, much

like the iconography and symbols discussed by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott

Brown, and Steven Izenour, punctuates the public space of the corridor as a

response to the everyday life of the city. As Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour

had done with the signage and graphic elements of the Las Vegas strip, I photographed

and cataloged the street art and faded iconography along Howard Street. Plywood

covered storefronts proved to be the most inviting canvases for street art, as

the highest percentage of art was found on the blocks with the most vacant

buildings. Whether it altered the environment for better or worse seems to be a

matter of personal preference, as I noted from my conversation with the passerby,

but its presence is certainly noticed.

Very little that

exists on Howard Street is consistent from Monument to Fayette. Street art, however,

is surprisingly abundant along the entire stretch. These images carry heavy

messages, which make them particularly intriguing. As I was studying one of the

first pieces I encountered, I paused photographing so as to greet a passerby.

The man said hello, continued walking to the opposite end of the block, then reversed

course with extreme purpose. He marched back to where I stood to ask me why I would

photograph this image which he didn’t find to be especially alluring. I’m very glad

he decided to speak with me, for our long discussion of art proved quite

enjoyable and as testimony of art’s power to bring strangers together. Art, much

like the iconography and symbols discussed by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott

Brown, and Steven Izenour, punctuates the public space of the corridor as a

response to the everyday life of the city. As Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour

had done with the signage and graphic elements of the Las Vegas strip, I photographed

and cataloged the street art and faded iconography along Howard Street. Plywood

covered storefronts proved to be the most inviting canvases for street art, as

the highest percentage of art was found on the blocks with the most vacant

buildings. Whether it altered the environment for better or worse seems to be a

matter of personal preference, as I noted from my conversation with the passerby,

but its presence is certainly noticed. A most exciting

study of Howard Street came from my consideration of nature in the city. My

evaluation was based on Anne Whiston Spirn’s belief that nature helps to

determine how meaningful a place may be. In my investigation, I paid particular

attention to nature as it specifically pertains to plant life. When observing an

open space inventory of Baltimore City as a whole, patches of green speckle the

map save for the area within which Howard Street rests (Baltimore

2010).

The only green spaces along this portion of the road are Howard’s Park,

directly across from the old Greyhound Terminal[2]. Outside

of Howard’s Park, nature has been left to fend for itself. Where street trees

once stood, empty wells mark the graves of

fallen allies. These empty tree wells have sometimes been filled with asphalt,

as if to ensure anything that lives can never grow there again. Occasionally,

perhaps in an attempt to conceal this atrocious behavior, flower pots have been

set on top of these asphalt-filled, empty tree wells. My investigation included

counting the total number of tree wells on each block, and how many of them

were actually filled with street trees. I discovered that the blocks with the

most vacant buildings were also those with the fewest occupied tree wells. I

determined that 17% of the tree wells on the 400 block from Franklin to

Mulberry were empty, and an astonishing 62% of the tree wells between Mulberry

and Saratoga were barren. In addition to street trees (or lack thereof), I

identified any instance where nature proved more resourceful than humans had accounted

for. It is not the property-owners of the northern blocks that have claimed

ownership of the land, it’s the land itself that has declared possession. In

these warm March days, hearty and verdant weeds have already begun to seep from

the cracks in the pavement. Even the asphalt filled wells couldn’t keep nature

from persevering: mature trees had found their way into abandoned buildings and

now escape through gaps in the boarded-up windows and out onto rooftops. The

six blocks between Monument and Fayette Streets account for a total length of

approximately 2,513 feet. Along this stretch of Howard Street, there is an

average of about one tree for every 40 feet. Not nearly enough, in my personal

opinion.

A most exciting

study of Howard Street came from my consideration of nature in the city. My

evaluation was based on Anne Whiston Spirn’s belief that nature helps to

determine how meaningful a place may be. In my investigation, I paid particular

attention to nature as it specifically pertains to plant life. When observing an

open space inventory of Baltimore City as a whole, patches of green speckle the

map save for the area within which Howard Street rests (Baltimore

2010).

The only green spaces along this portion of the road are Howard’s Park,

directly across from the old Greyhound Terminal[2]. Outside

of Howard’s Park, nature has been left to fend for itself. Where street trees

once stood, empty wells mark the graves of

fallen allies. These empty tree wells have sometimes been filled with asphalt,

as if to ensure anything that lives can never grow there again. Occasionally,

perhaps in an attempt to conceal this atrocious behavior, flower pots have been

set on top of these asphalt-filled, empty tree wells. My investigation included

counting the total number of tree wells on each block, and how many of them

were actually filled with street trees. I discovered that the blocks with the

most vacant buildings were also those with the fewest occupied tree wells. I

determined that 17% of the tree wells on the 400 block from Franklin to

Mulberry were empty, and an astonishing 62% of the tree wells between Mulberry

and Saratoga were barren. In addition to street trees (or lack thereof), I

identified any instance where nature proved more resourceful than humans had accounted

for. It is not the property-owners of the northern blocks that have claimed

ownership of the land, it’s the land itself that has declared possession. In

these warm March days, hearty and verdant weeds have already begun to seep from

the cracks in the pavement. Even the asphalt filled wells couldn’t keep nature

from persevering: mature trees had found their way into abandoned buildings and

now escape through gaps in the boarded-up windows and out onto rooftops. The

six blocks between Monument and Fayette Streets account for a total length of

approximately 2,513 feet. Along this stretch of Howard Street, there is an

average of about one tree for every 40 feet. Not nearly enough, in my personal

opinion.

Other systems of

observation were less fruitful. The study area lacked many of the layers that

would define any of the elements architect Christopher Alexander might identify

as terminology of a pattern language. Certainly this lack of patterns, however,

contributes to the area’s absent vitality. Hierarchy of spaces can be

experienced close to the Market, but on the northern blocks the space is void.

As I review my findings from the various systems of evaluation, I find

reinforcement of the intuitive perception that it is the absence of a number of systems which make certain environments less

productive.

Oddly enough, however, the total absence of layers is also what

contributes to the haven-like atmosphere of the northern blocks. The two blocks

between Mulberry and Centre lack nearly all layers of environmental character,

including people. Deserted spaces in cities usually connote an unsafe territory,

yet these blocks have just the right amount of people riding by on the light

rail and walking past on their trips to the area’s various attractions that the

blocks offer safe solitude for any urbanite in search of refuge. How peculiar

it is to be in a dense urban setting without all the commotion of frenzied city

life!?

Future Study and Final Thoughts

The element of

life, both human and natural, is an important assessment of a location’s well

being. Had I more time to study this portion of Howard Street, I would take a

cyclical approach. I would consider changes of the natural seasons and note how

they may or may not shape the level of pedestrian activity. Such an analysis should

be continued for a span of many years, and should be critical of the ways in

which human behavior is altered by any changes in environment. There is also

potential for more normative, detailed statistical research on the tree canopy

of the area and about the life stages of the trees on each block. This data

could be compared with that of Baltimore City as a whole. By further developing

a study of life as it exists on Howard Street, overlays of information illustrate

an urban environments success and failure.

Today, Howard

Street struggles, yet it works. It works as an exhibit of sorts through which

someone might stroll to discover something new about their city, or themselves.

The unfortunate truth, however, is that although these crumbling facades paint

a picture of the exciting corridor that Howard Street had once been, their

symptoms of disrepair also warn of a disastrous future.

Bibliography

Baltimore,

Downtown Partnership of. "Downtown Open Space Plan." Baltimore, MD,

2010.

Bejgrowicz, Tom. "Tom B Photography." Blogspot.

May 31, 2009.

http://tombphotography.blogspot.com/2009/05/mayfair-theater-i-balt.html

(accessed March 9, 2012).

Gunts, Edward. "Mayfair Could Anchor 'Avenue of the

Arts'." The Baltimore Sun. November 4, 1993.

http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1993-11-04/news/1993308101_1_mayfair-center-for-theater-towson

(accessed March 9, 2012).

Pousson, Eli. "Why the West Side Matters: Read’s Drug

Store and Baltimore’s Civil Rights Heritage." Baltimore Heritage.

January 7, 2011.

http://www.baltimoreheritage.org/2011/01/why-the-west-side-matters-reads-drug-store-and-baltimores-civil-rights-heritage/

(accessed March 9, 2012).

Vandervoort, Bill. Classic Bus Stations.

http://web.me.com/willvdv/chirailfan/greystne.html (accessed March 9, 2012).

[1] A

majority of this information has been gathered from personal discussions and

general inquiries. Further research is required for verification.

[2]

The study also identifies the Metro Station plaza as open space on the map, although this hardly accounts for any green space.

The above text is from a written report describing the conditions along Howard Street, Baltimore through use of the methods proposed by various urban theorists. It was an assignment from an Urban Design Studio course in Morgan State University's City and Regional Planning Graduate program.

The above text is from a written report describing the conditions along Howard Street, Baltimore through use of the methods proposed by various urban theorists. It was an assignment from an Urban Design Studio course in Morgan State University's City and Regional Planning Graduate program.

Saturday, February 11, 2012

Hoping for Howard Street

This semester, my urban design course will be looking at this corridor. While I've been there dozens of times in the last few months alone, I rarely look deeply at the obvious wounds and scars. Instead, I usually admire how beautiful the architectural detail is on each crumbling building, and my imagination takes me to a place I've only ever been told about, a thriving retail center for an entire region. It must have been wonderful, and I've seen photographs that certainly look inviting! Today, however, it's nothing like it used to be. While businesses are speckled among the first floors of some buildings, most appear to be struggling, and very few cater to everyday needs. Furthermore, above these establishments, the remaining 3 or more floors of each building are left vacant. Interjecting between the storefronts is a threatening wall of plywood, blocking off the entirely vacant structures. Some blocks are better off than others, sometimes even one side of the street is more fortunate than the opposite, but the overall feeling is one of despair.

|

| In front of the old Mayfair Theater |

|

| The art in question, raw street art, or movie posters? |

|

| An absolutely beautiful piece of street art fronting Franklin |

Served well by transit, this area has so much opportunity to be a destination for all city residents, to draw suburbanites into the downtown area, and to serve the current residents of the area. There is much to be done.

Tuesday, February 7, 2012

Cleaning and Greening in Baltimore City

This semester, I am fortunate enough to be working as a graduate assistant under my department chairperson of the City and Regional Planning Program. If I have not yet mentioned this before, I'm a student at Morgan State University, an HBCU in Baltimore. So far, the program has been terrific, and this, my second semester, has already proven to be exciting. Most of the excitement comes from a university-wide initiative to reconnect our school with the surrounding community. This is the project for which I am assisting my chair. We have an economic development grant and are researching and evaluating the communities surrounding MSU. These communities make up most of the Northeast quadrant of Baltimore city. Yesterday, we held a board meeting with representatives from local community associations. At this meeting, I had heard so many varying viewpoints, and learned so much about this city.

I was actually surprised to hear about the rising interest in some of the things that an environmental urbanist values: buying local, eating organic and healthy, and keeping the city green.A few years ago, Baltimore City launched the initiative "Cleaner, Greener Baltimore." Unfortunately, it hasn't gotten as much media hype as many would have hoped. But that doesn't mean that city residents haven't taken it's values to heart. Whether or not they do it for sustainability or environmental issues, city residents are actively "cleaning and greening" their neighborhoods. Sometimes, the city will be able to pay for these activities, but when the city can't, the residents fork up their own dollars to bring dumpsters in to dispose of recyclables and waste.

There are numerous other initiatives and programs in the city. Most weren't created for sustainability reasons, but all immediately effect the environment in positive ways. The Vacants to Value program enacted by Mayor Rawlings Blake encourages vacant spaces- which often become dumping grounds for trash- to be revitalized and occupied. This improves the livability of our city, making it a more viable place to live and invest in. The Department of Transportation (DOT) has also been "greening" the streetscapes by implementing storm water management technologies. These were introduced to control our cities terrible storm water issues (due to the extreme lack of natural and porous surfaces), and it's definitely a wonderful program for people like myself, who hope to see even more environmental initiatives pop up over the years, to hear about.

The assistantship will hopefully continue to expose me to the many different programs and opportunities Baltimore currently has that benefit the environment while at the same time strengthening our city.

I was actually surprised to hear about the rising interest in some of the things that an environmental urbanist values: buying local, eating organic and healthy, and keeping the city green.A few years ago, Baltimore City launched the initiative "Cleaner, Greener Baltimore." Unfortunately, it hasn't gotten as much media hype as many would have hoped. But that doesn't mean that city residents haven't taken it's values to heart. Whether or not they do it for sustainability or environmental issues, city residents are actively "cleaning and greening" their neighborhoods. Sometimes, the city will be able to pay for these activities, but when the city can't, the residents fork up their own dollars to bring dumpsters in to dispose of recyclables and waste.

There are numerous other initiatives and programs in the city. Most weren't created for sustainability reasons, but all immediately effect the environment in positive ways. The Vacants to Value program enacted by Mayor Rawlings Blake encourages vacant spaces- which often become dumping grounds for trash- to be revitalized and occupied. This improves the livability of our city, making it a more viable place to live and invest in. The Department of Transportation (DOT) has also been "greening" the streetscapes by implementing storm water management technologies. These were introduced to control our cities terrible storm water issues (due to the extreme lack of natural and porous surfaces), and it's definitely a wonderful program for people like myself, who hope to see even more environmental initiatives pop up over the years, to hear about.

The assistantship will hopefully continue to expose me to the many different programs and opportunities Baltimore currently has that benefit the environment while at the same time strengthening our city.

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

I'm currently applying to the Castle Ink Paperless Scholarship to help me fund my education- which, by the way, is why I haven't been able to post much lately! I'm earning my Master's Degree in City and Regional Planning and specializing in Sustainable Cities. I truly love learning about this stuff, and I can't wait to apply my knowledge.

To fund my school, I've begun looking for scholarships that really define who I am, and this scholarship from Castle Ink (http://www.castleink.com) does just that! For all of those who know me, I am very much a part of the reduce, reuse, recycle mindset. That mantra comes into play in every aspect of my life, everyday. I start my limiting how much I own, and what I buy. I buy only what's necessary, and I buy what comes with the least amount of packaging, a.k.a. waste. When I'm finished with something, I sell it, trade it, donate it, or reuse it. DIY crafts, baby! Up-cycling and re-purposing are my hobbies since childhood! As for everything I can not find a second use for, I recycle!

I've been successful in encouraging and beginning workplace recycling at my jobs, and I always do my best to teach friends and family about what they can do to help (of course, my family were the ones who taught me in the first place! Thanks, Mom and Dad!).

The point is, you can, and should, live by this mantra as well. To be honest, it makes life richer- in every sense of the term!!

To fund my school, I've begun looking for scholarships that really define who I am, and this scholarship from Castle Ink (http://www.castleink.com) does just that! For all of those who know me, I am very much a part of the reduce, reuse, recycle mindset. That mantra comes into play in every aspect of my life, everyday. I start my limiting how much I own, and what I buy. I buy only what's necessary, and I buy what comes with the least amount of packaging, a.k.a. waste. When I'm finished with something, I sell it, trade it, donate it, or reuse it. DIY crafts, baby! Up-cycling and re-purposing are my hobbies since childhood! As for everything I can not find a second use for, I recycle!

I've been successful in encouraging and beginning workplace recycling at my jobs, and I always do my best to teach friends and family about what they can do to help (of course, my family were the ones who taught me in the first place! Thanks, Mom and Dad!).

The point is, you can, and should, live by this mantra as well. To be honest, it makes life richer- in every sense of the term!!

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

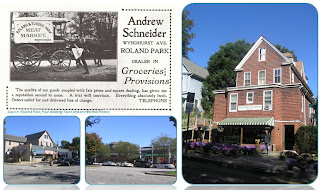

Roland Park: A National Model

In north Baltimore, there lies a community of well designed homes guarded by the spirits of old trees. Nearby the hustle and bustle of the crowded harbor, it's a literal breath of fresh air. There are many who call this area home, and home it has been for over 100 years. Roland Park is a residential neighborhood that was built in Baltimore at the end of the 19th century. An area of natural beauty made accessible by rail, Roland Park became a place of carefully planned, gently-curving streets; a collection of single family homes sited wisely on large lots of land; and grand expressions of civic beauty. The elements of Roland Park's design can clearly be related to important historical planning movements- the Urban Parks, Garden City, and City Beautiful movements of the 19th century- as well as to movements happening today, such as the New Urbanism.

In 1890, William Edmunds, president of the Baltimore newspaper, Manufacturer's Record, owned land just north of what was then the Baltimore City boundary. At this time, Baltimore was already a busy and congested city. The charter for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad six decades prior had made Baltimore a major shipping and manufacturing center in the country. Like many other cities at the turn of the century, Baltimore had a plethora of harrowing conditions. As people were moving into cities in decades past, hoping to find economic opportunities, those who could now afford it were leaving the cities to seek residence away from the factories and filth of the central city districts. With the extension of rail lines, the land Edmunds owned would be a daily escape that had previously only existed for the wealthy owners of summer and weekend cottages. He was hoping to subdivide and develop 100 acres of this land and came across the opportunity through a man by the name of Charles Grastly. Having recently moved to Baltimore from Kansas City, MO, Grastly met Edmunds through his position as editor of the Baltimore Evening News. Grastly had connections back in Kansas City that could start the development of Edmund's land. The Jarvis-Conklin Mortgage Trust Company, with which Grastly had previous land speculation experience, financed the project along with an investment from an English business syndicate. To start off the development, Jarvis and Conklin selected Edward Bouton as general manager and appointed George E. Kessler to the position of lead architect; and so the Roland Park- Kansas City link was established. In Baltimore, these men formed the Roland Park Company and the development of Roland Park, named after Roland Thornberry, a Baltimore County landowner, had commenced that same year (Lewand, 1).

Falls Turnpike, known today as Falls road, was lengthened and renovated in 1805 after the Falls Turnpike Charter was approved. A year later, Coldspring Lane was created. Together, these two thoroughfares made the area of today's Roland Park accessible where the hilly terrain had previously kept it from being so. In 1890, the development began with Plat 1, the area extending just north of Coldspring Lane and to the east of Roland Ave. This section of Roland Park was designed by the Jarvis and Conklin chosen architect, George Kessler. Before studying in Germany, Kessler spent some time in the 1880s training under the well-known landscape designer, Frederick Law Olmsted. Kessler had a bit of Olmsted's landscape intuition, and in Roland Park's design was able to "blend the curvilinear and the formal in the same parkway without breaking its continuity" (Wilson, 108). Together with Bouton's strong emphasis on preserving the existing scenery, Kessler's plans created a revolutionary new lifestyle. This lifestyle went hand in hand with the growing consensus that by living near parks, people would become healthier and happier. In Roland Park, however, residents didn't just live near a park, they could live in the park.

Club Road; Picturesque and curving

As a reaction to the unsanitary conditions growing in cities during the early 19th century, figures like Frederick Law Olmsted stressed the need for sunlight and open air, arguing that natural spaces gave city residents opportunities for leisure as well as a release from the filth of city life. This idea was the fuel behind what became the Urban Parks Movement. At the beginning of Roland Park’s inception, Frederick Law Olmsted was merely an influence, having spent some time training Kessler. It wouldn't be until the development of Plat 2 that Frederick Law Olmsted had more direct control in Roland Park through the hands of his sons, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and John Charles Olmsted. In 1897, when Plat 2 was in the works, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and John Charles, son and stepson respectively, had acquired Olmsted's practice upon his retirement in 1894. The Olmsted Brothers firm became the leading architect for Roland Park. Though Kessler's designs for Plat 1 were reminiscent of the picturesque quality often found in Olmsted's work, it was still more traditional in its design. The land of Plat 1 was fairly flat and bounded by two parallel, arterial right-of-ways. It did not require "unusually creative site planning," as would the later plats created by the Olmsted Brothers. With the rejection of the city grid system of laying out roadways and its emphasis on natural elements, Roland Park had become a Romantic Suburb, with winding lands and the feeling of being immersed in nature (Messner).Romantic Suburbs were communities planned in picturesque settings. The resembled the landscapes of English Gardens, which had so influenced landscape designers of the time. Romantic Suburbs were harmonious communities, "...a complete environment that fulfilled expectations of a tranquil life, close to nature, with urban comforts" (Jackson, 86).

At the same time that Roland Park was being developed, another planning concept was gaining popularity in Europe. Starting in England, the Garden City movement was introduced by Sir Ebenezer Howard with the publication of his book, Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. Howard's Garden City idea was one of social progress. Having spent some time in America during the Homestead Act, Howard had been inspired by Olmsted's work (Legates, 309). Upon returning home, Howard was exposed to the ideas of Utopian Socialism. He took the need for parks that had been stressed by Olmsted and added to it the need for social housing. Howard "added a new element to the rights of man- the right to space" (Campbell, 42). He had felt cities were in need of great change. Cities were the cause of our social issues, and the Garden City was the solution. By moving populations of no more than 32,000 people into centralized cores outside of- and separated by green belts from- cities, societal and housing issues could be addressed and corrected.

The Garden City, Howard explained, would be a self-sufficient community, economically independent from other cities. Howard gathered his idea from the comparison of country life to town life. The country was expansive and beautiful. It was, he felt, created by a higher power. The shortcoming of the country was that it was too rural. Living in the country was inconvenient in an age of rising technology. The town, on the other hand, was the symbol of society. Yet society, as we know, had many issues. Howard saw more than just these two alternatives; he saw a combination of the two, the Town-Country. "Town and Country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilization"(Howard). Roland Park was a great example of this union: each home was surrounded by nature while everything the city had to offer was a mere 20 minute train ride away.

Roland Park's shortcoming, in terms of these ideals, was that it lacked some of the better amenities the town had to offer. Residents still had to travel into the city quite often for work and often for large purchases. In fact, residents needed to do so. Bouton permitted, "only those businesses which are necessary for the comfort of our residents"(Master Plan). Though a few shops and amenities were available within Roland Park, most needs would have provoked a train ride to one of Baltimore's central business districts, such as the one along Howard Street. Also in Howard's Garden City, there would be opportunities for leisure; but the residents of these "houses in a park," unlike those in the Romantic Suburbs, did not individually own the green space out their front door. This land, instead, belonged to the community, with a Garden City Company as the sole landlord. Some similarities can be drawn between Roland Park Company and Howard's idea for a Garden City Company, such as the strict covenant they both transcribed, but it was not quite the same.

Shopping opportunities in and adjacent to Roland Park

Quite an important concept of the movement, Howard's Garden City would be a place for everyone. This was far from the truth in Roland Park. Sadly, "the suburban world of leisure, family life, and union with nature was based on the principle of exclusion"(Fishman, 4). With the strict and legally mandatory covenant introduced by Bouton and the Roland Park Company, Roland Park legally excluded many groups of people. In 1910, residents were required to sign the covenant, which excluded African Americans. In that same year, department stores were segregated and racial tensions were most extreme. Three years later, Jewish residents were also barred. Unfortunately, Roland Park had set an example and many other Baltimore neighborhoods would soon follow this model. But it was not only the covenant that kept out certain people; the houses generally had a minimum value, making them unaffordable for some (Ames). This requirement, in addition to the fact that the cost of commuting by rail, though not entirely unmanageable, meant living in Roland Park was too expensive of a lifestyle for most members of the working class. This lifestyle became an expression of the upper class. With the establishment of the Baltimore Country Club in 1898, this separation of classes was exaggerated even more.

The Garden City movement had made its way back across the Atlantic to America, but it wasn't until a few decades later. By the 1900s, Roland Park was well underway, and so it's not very likely the movement had much influence on Roland Park's designs. One thing, however, can be said of Roland Park and the Garden City Movement: it is alike other Garden City developments in that nearly all Garden City endeavors failed to meet the principles outlined by Howard. Most attempts at Garden City design are better classified as Garden Suburbs, rather than Garden Cities. These places were still almost wholly dependent on nearby cities; they were not as large as Howard's Garden City populated by 30,000; in fact, they were quite the exact opposite of what Howard prescribed for his Garden Cities. It's hard to ignore the patterns of certain blocks in Roland Park and how they resemble these sorts of derivatives of Howard's concept. It may perhaps be coincidental and not at all because of direct influence, but the designs of areas like Merryman's Court and Ridgewood Corner, in Plats 5 and 2, are surprisingly comparable to developments like Hampstead Garden Suburb, the first Garden Suburb. In these two parts of Roland Park, a grouping of houses are set facing a common green area, a frequent element used in Garden Cities. Even the architectural styles are evocative of the English vernacular architecture used in Hampstead and other Garden Suburbs. In regards to its social intentions, the Garden City movement cannot be clearly seen in Roland Park. The common Garden Suburb, however, and Roland Park can be equated.

Just three years after the members of the Roland Park Company had come together, something grand was happing in the Midwest. In 1893, The World's Columbian Exposition had opened in Chicago. The Expo is best known for its impressive architecture, emphasis on civic design, and the Beaux Arts value of joining disciplines- art, architecture, sculpture, landscape design- in the city development process. These principles became a part of the City Beautiful Movement. The resulting designs expressed grand, neoclassical architecture; civic monuments; and the establishment of cultural institutions. The influence of the City Beautiful Movement is more obvious in the cultural buildings of Roland Park, such as the Enoch Pratt library, the municipal water tower, and St. Mary's Seminary- the last of these three being perhaps the best example of City Beautiful architecture, and one of Baltimore's most recognizable landmarks today. The homes along Goodwood Gardens, West of Roland Park, a street once referred to as "Millionaire's Row," are also great examples of this movement. Their designs are grand explorations in residential architecture. For the most part, however, Roland Park residences were humble, yet sophisticated structures rather than an exploration of the City Beautiful.

Similarities between a Garden City and Roland Park

In 1940, the rail line was removed from Roland Avenue as the automobile had become the frontrunner in intra-city travel. Eight years later, the Supreme Court ruled that the restrictive covenant which restricted African Americans and Jews from living in Roland Park was illegal. Roland Park has gone through some changes, but for the most part remains unchanged. Many original trees still remain, and ones planted by Bouton have since grown. It's likely Roland Park wouldn't look anything like this today if it weren't for the strict covenants and careful planning that went into its design. And it is precisely that planning that has given Roland Park the status it holds today as one of the earliest planned communities that happens to be home to the nation's first shopping center. It has been a model and leader for many communities to follow. As we've seen with the racially barring covenant, that hasn't always been proven a good thing. However, Roland Park had been inspiration for communities across the country and remains so today. With modern-day planning movements, it is a reference. The narrow paths set behind houses serve as service lanes where the unattractive necessities of single family living (trash pick-up, electrical wiring, and automobile parking) can take place. This is a practice that the New Urbanists currently promote in their Traditional Neighborhood Developments.

Garage access via service lane

Whether for good or for ill, Roland Park has always been of an exemplary design. It was a learning process from the beginning, and we have certainly gained the issues it met and how they were overcome. A model community of various planning movements, the neighborhood has received recognition many times over. Now, holding national status, this old neighborhood in Baltimore continues to mature and grows ever more romantic, garden-like, and beautiful.

Bibliography:

Ames, David L., and Linda F. McClelland. "National Register Bureau Suburbs Part 2: Historic Residential Suburbs: Guidelines for Evaluation and Documentation for the National Register of Historic Places." U.S. National Park Service - Experience Your America. National Register Publications, 2002. Web. 10 Oct.

Campbell, Scott, and Susan S. Fainstein. Readings in Planning Theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003.

Howard, Ebenezer. To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: the Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford UP, 1985.

LeGates, Richard T., and Frederic Stout. The City Reader. London: Routledge, 2007.

Lewand, Karen. North Baltimore, from Estate to Development. Ed. D. Randall. Beirne. Baltimore, MD: Prepared by Baltimore City Department of Planning and the University of Baltimore, 1989.

Messner, Rebecca. "Olmsted's Shortcuts | General Home & Design." Urbanite Baltimore Magazine. 1 July 2011. Web. 14 Sept. 2011.

Roland Park Civic League. Greater Roland Park Master Plan. Baltimore, 2010. Print.

Wilson, William H. The City Beautiful Movement. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, MD, 1989.

The above text and presentation images are from a report studying an historic Baltimore City project [my chosen project being the planned community of Roland Park] as its creation and development relate to planning movements. It is the resulting coursework of an History of City and Regional Planning seminar in Morgan State University's City and Regional Planning Graduate Program.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)