Thursday, October 27, 2011

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Roland Park: A National Model

In north Baltimore, there lies a community of well designed homes guarded by the spirits of old trees. Nearby the hustle and bustle of the crowded harbor, it's a literal breath of fresh air. There are many who call this area home, and home it has been for over 100 years. Roland Park is a residential neighborhood that was built in Baltimore at the end of the 19th century. An area of natural beauty made accessible by rail, Roland Park became a place of carefully planned, gently-curving streets; a collection of single family homes sited wisely on large lots of land; and grand expressions of civic beauty. The elements of Roland Park's design can clearly be related to important historical planning movements- the Urban Parks, Garden City, and City Beautiful movements of the 19th century- as well as to movements happening today, such as the New Urbanism.

In 1890, William Edmunds, president of the Baltimore newspaper, Manufacturer's Record, owned land just north of what was then the Baltimore City boundary. At this time, Baltimore was already a busy and congested city. The charter for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad six decades prior had made Baltimore a major shipping and manufacturing center in the country. Like many other cities at the turn of the century, Baltimore had a plethora of harrowing conditions. As people were moving into cities in decades past, hoping to find economic opportunities, those who could now afford it were leaving the cities to seek residence away from the factories and filth of the central city districts. With the extension of rail lines, the land Edmunds owned would be a daily escape that had previously only existed for the wealthy owners of summer and weekend cottages. He was hoping to subdivide and develop 100 acres of this land and came across the opportunity through a man by the name of Charles Grastly. Having recently moved to Baltimore from Kansas City, MO, Grastly met Edmunds through his position as editor of the Baltimore Evening News. Grastly had connections back in Kansas City that could start the development of Edmund's land. The Jarvis-Conklin Mortgage Trust Company, with which Grastly had previous land speculation experience, financed the project along with an investment from an English business syndicate. To start off the development, Jarvis and Conklin selected Edward Bouton as general manager and appointed George E. Kessler to the position of lead architect; and so the Roland Park- Kansas City link was established. In Baltimore, these men formed the Roland Park Company and the development of Roland Park, named after Roland Thornberry, a Baltimore County landowner, had commenced that same year (Lewand, 1).

Falls Turnpike, known today as Falls road, was lengthened and renovated in 1805 after the Falls Turnpike Charter was approved. A year later, Coldspring Lane was created. Together, these two thoroughfares made the area of today's Roland Park accessible where the hilly terrain had previously kept it from being so. In 1890, the development began with Plat 1, the area extending just north of Coldspring Lane and to the east of Roland Ave. This section of Roland Park was designed by the Jarvis and Conklin chosen architect, George Kessler. Before studying in Germany, Kessler spent some time in the 1880s training under the well-known landscape designer, Frederick Law Olmsted. Kessler had a bit of Olmsted's landscape intuition, and in Roland Park's design was able to "blend the curvilinear and the formal in the same parkway without breaking its continuity" (Wilson, 108). Together with Bouton's strong emphasis on preserving the existing scenery, Kessler's plans created a revolutionary new lifestyle. This lifestyle went hand in hand with the growing consensus that by living near parks, people would become healthier and happier. In Roland Park, however, residents didn't just live near a park, they could live in the park.

Club Road; Picturesque and curving

As a reaction to the unsanitary conditions growing in cities during the early 19th century, figures like Frederick Law Olmsted stressed the need for sunlight and open air, arguing that natural spaces gave city residents opportunities for leisure as well as a release from the filth of city life. This idea was the fuel behind what became the Urban Parks Movement. At the beginning of Roland Park’s inception, Frederick Law Olmsted was merely an influence, having spent some time training Kessler. It wouldn't be until the development of Plat 2 that Frederick Law Olmsted had more direct control in Roland Park through the hands of his sons, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and John Charles Olmsted. In 1897, when Plat 2 was in the works, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and John Charles, son and stepson respectively, had acquired Olmsted's practice upon his retirement in 1894. The Olmsted Brothers firm became the leading architect for Roland Park. Though Kessler's designs for Plat 1 were reminiscent of the picturesque quality often found in Olmsted's work, it was still more traditional in its design. The land of Plat 1 was fairly flat and bounded by two parallel, arterial right-of-ways. It did not require "unusually creative site planning," as would the later plats created by the Olmsted Brothers. With the rejection of the city grid system of laying out roadways and its emphasis on natural elements, Roland Park had become a Romantic Suburb, with winding lands and the feeling of being immersed in nature (Messner).Romantic Suburbs were communities planned in picturesque settings. The resembled the landscapes of English Gardens, which had so influenced landscape designers of the time. Romantic Suburbs were harmonious communities, "...a complete environment that fulfilled expectations of a tranquil life, close to nature, with urban comforts" (Jackson, 86).

At the same time that Roland Park was being developed, another planning concept was gaining popularity in Europe. Starting in England, the Garden City movement was introduced by Sir Ebenezer Howard with the publication of his book, Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. Howard's Garden City idea was one of social progress. Having spent some time in America during the Homestead Act, Howard had been inspired by Olmsted's work (Legates, 309). Upon returning home, Howard was exposed to the ideas of Utopian Socialism. He took the need for parks that had been stressed by Olmsted and added to it the need for social housing. Howard "added a new element to the rights of man- the right to space" (Campbell, 42). He had felt cities were in need of great change. Cities were the cause of our social issues, and the Garden City was the solution. By moving populations of no more than 32,000 people into centralized cores outside of- and separated by green belts from- cities, societal and housing issues could be addressed and corrected.

The Garden City, Howard explained, would be a self-sufficient community, economically independent from other cities. Howard gathered his idea from the comparison of country life to town life. The country was expansive and beautiful. It was, he felt, created by a higher power. The shortcoming of the country was that it was too rural. Living in the country was inconvenient in an age of rising technology. The town, on the other hand, was the symbol of society. Yet society, as we know, had many issues. Howard saw more than just these two alternatives; he saw a combination of the two, the Town-Country. "Town and Country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilization"(Howard). Roland Park was a great example of this union: each home was surrounded by nature while everything the city had to offer was a mere 20 minute train ride away.

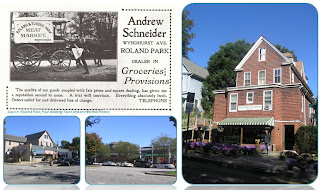

Roland Park's shortcoming, in terms of these ideals, was that it lacked some of the better amenities the town had to offer. Residents still had to travel into the city quite often for work and often for large purchases. In fact, residents needed to do so. Bouton permitted, "only those businesses which are necessary for the comfort of our residents"(Master Plan). Though a few shops and amenities were available within Roland Park, most needs would have provoked a train ride to one of Baltimore's central business districts, such as the one along Howard Street. Also in Howard's Garden City, there would be opportunities for leisure; but the residents of these "houses in a park," unlike those in the Romantic Suburbs, did not individually own the green space out their front door. This land, instead, belonged to the community, with a Garden City Company as the sole landlord. Some similarities can be drawn between Roland Park Company and Howard's idea for a Garden City Company, such as the strict covenant they both transcribed, but it was not quite the same.

Shopping opportunities in and adjacent to Roland Park

Quite an important concept of the movement, Howard's Garden City would be a place for everyone. This was far from the truth in Roland Park. Sadly, "the suburban world of leisure, family life, and union with nature was based on the principle of exclusion"(Fishman, 4). With the strict and legally mandatory covenant introduced by Bouton and the Roland Park Company, Roland Park legally excluded many groups of people. In 1910, residents were required to sign the covenant, which excluded African Americans. In that same year, department stores were segregated and racial tensions were most extreme. Three years later, Jewish residents were also barred. Unfortunately, Roland Park had set an example and many other Baltimore neighborhoods would soon follow this model. But it was not only the covenant that kept out certain people; the houses generally had a minimum value, making them unaffordable for some (Ames). This requirement, in addition to the fact that the cost of commuting by rail, though not entirely unmanageable, meant living in Roland Park was too expensive of a lifestyle for most members of the working class. This lifestyle became an expression of the upper class. With the establishment of the Baltimore Country Club in 1898, this separation of classes was exaggerated even more.

The Garden City movement had made its way back across the Atlantic to America, but it wasn't until a few decades later. By the 1900s, Roland Park was well underway, and so it's not very likely the movement had much influence on Roland Park's designs. One thing, however, can be said of Roland Park and the Garden City Movement: it is alike other Garden City developments in that nearly all Garden City endeavors failed to meet the principles outlined by Howard. Most attempts at Garden City design are better classified as Garden Suburbs, rather than Garden Cities. These places were still almost wholly dependent on nearby cities; they were not as large as Howard's Garden City populated by 30,000; in fact, they were quite the exact opposite of what Howard prescribed for his Garden Cities. It's hard to ignore the patterns of certain blocks in Roland Park and how they resemble these sorts of derivatives of Howard's concept. It may perhaps be coincidental and not at all because of direct influence, but the designs of areas like Merryman's Court and Ridgewood Corner, in Plats 5 and 2, are surprisingly comparable to developments like Hampstead Garden Suburb, the first Garden Suburb. In these two parts of Roland Park, a grouping of houses are set facing a common green area, a frequent element used in Garden Cities. Even the architectural styles are evocative of the English vernacular architecture used in Hampstead and other Garden Suburbs. In regards to its social intentions, the Garden City movement cannot be clearly seen in Roland Park. The common Garden Suburb, however, and Roland Park can be equated.

Just three years after the members of the Roland Park Company had come together, something grand was happing in the Midwest. In 1893, The World's Columbian Exposition had opened in Chicago. The Expo is best known for its impressive architecture, emphasis on civic design, and the Beaux Arts value of joining disciplines- art, architecture, sculpture, landscape design- in the city development process. These principles became a part of the City Beautiful Movement. The resulting designs expressed grand, neoclassical architecture; civic monuments; and the establishment of cultural institutions. The influence of the City Beautiful Movement is more obvious in the cultural buildings of Roland Park, such as the Enoch Pratt library, the municipal water tower, and St. Mary's Seminary- the last of these three being perhaps the best example of City Beautiful architecture, and one of Baltimore's most recognizable landmarks today. The homes along Goodwood Gardens, West of Roland Park, a street once referred to as "Millionaire's Row," are also great examples of this movement. Their designs are grand explorations in residential architecture. For the most part, however, Roland Park residences were humble, yet sophisticated structures rather than an exploration of the City Beautiful.

Similarities between a Garden City and Roland Park

In 1940, the rail line was removed from Roland Avenue as the automobile had become the frontrunner in intra-city travel. Eight years later, the Supreme Court ruled that the restrictive covenant which restricted African Americans and Jews from living in Roland Park was illegal. Roland Park has gone through some changes, but for the most part remains unchanged. Many original trees still remain, and ones planted by Bouton have since grown. It's likely Roland Park wouldn't look anything like this today if it weren't for the strict covenants and careful planning that went into its design. And it is precisely that planning that has given Roland Park the status it holds today as one of the earliest planned communities that happens to be home to the nation's first shopping center. It has been a model and leader for many communities to follow. As we've seen with the racially barring covenant, that hasn't always been proven a good thing. However, Roland Park had been inspiration for communities across the country and remains so today. With modern-day planning movements, it is a reference. The narrow paths set behind houses serve as service lanes where the unattractive necessities of single family living (trash pick-up, electrical wiring, and automobile parking) can take place. This is a practice that the New Urbanists currently promote in their Traditional Neighborhood Developments.

Garage access via service lane

Whether for good or for ill, Roland Park has always been of an exemplary design. It was a learning process from the beginning, and we have certainly gained the issues it met and how they were overcome. A model community of various planning movements, the neighborhood has received recognition many times over. Now, holding national status, this old neighborhood in Baltimore continues to mature and grows ever more romantic, garden-like, and beautiful.

Bibliography:

Ames, David L., and Linda F. McClelland. "National Register Bureau Suburbs Part 2: Historic Residential Suburbs: Guidelines for Evaluation and Documentation for the National Register of Historic Places." U.S. National Park Service - Experience Your America. National Register Publications, 2002. Web. 10 Oct.

Campbell, Scott, and Susan S. Fainstein. Readings in Planning Theory. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003.

Howard, Ebenezer. To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: the Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford UP, 1985.

LeGates, Richard T., and Frederic Stout. The City Reader. London: Routledge, 2007.

Lewand, Karen. North Baltimore, from Estate to Development. Ed. D. Randall. Beirne. Baltimore, MD: Prepared by Baltimore City Department of Planning and the University of Baltimore, 1989.

Messner, Rebecca. "Olmsted's Shortcuts | General Home & Design." Urbanite Baltimore Magazine. 1 July 2011. Web. 14 Sept. 2011.

Roland Park Civic League. Greater Roland Park Master Plan. Baltimore, 2010. Print.

Wilson, William H. The City Beautiful Movement. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, MD, 1989.

The above text and presentation images are from a report studying an historic Baltimore City project [my chosen project being the planned community of Roland Park] as its creation and development relate to planning movements. It is the resulting coursework of an History of City and Regional Planning seminar in Morgan State University's City and Regional Planning Graduate Program.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)